Everybody Gets A Chance

Order on Amazon Now

Need a break? "Everybody Gets A Chance", new short fiction from an author who’s been reviewed as writing, "...the funniest book I’ve read this year...."

Told in ten short stories and a novella, we meet a cross-section of the lost souls that have made America what it is today.

Whether it’s a swindled, hoodwinked young cabinet maker, choosing between his first serious relationship or a college education, or an on-the-lam campus protestor, forming her own band of half-baked eco-terrorists, or a burned-out lawyer, trying to save a community from an attack by a deranged anti-vaxxer, the characters in “Everybody Gets a Chance” have one thing in common: A reluctant conviction that all is not quite right with the World, and it’s their job to put the planet back on its axis.

CHAPTER 3

See what I mean? Breathtaking, I know….

So, first I enrolled in the local Methodist Seminary, figur- ing it would be manageable in my spare time, expecting it to be populated with noble people with sacred thoughts and bibles in their book bags.

Well, I met some really interesting people in Seminary, and, no, that’s not meant as a compliment. And, I quickly flunked out. Like a guy who doesn’t want to admit he got his black eye smacking into the fridge door looking for a beer, I’d like to say my expulsion arose when I narrowly escaped getting burned at the stake for blasphemy, but things just got busy at work and then I missed most of the exams. I thought a bunch of folks so dedicated to Godliness would find it within their hearts to never flunk anybody, but I got a computer-generated grade report in the mail that had the word “TERMINATED” stamped across it in big red letters. My theological report card actually looked like it was printed in blood, like the Seminary management might just be a bunch of closet Pagans doing ritual human sacrifice, so I took my lumps and never looked back.

Drifting aimlessly as I was, the record label thing still came about mostly by accident. My boss, an old guy who’d run the actuarial firm for decades and had a 1940’s, knee-slapping sense of humor, wanted to record some tongue-in-cheek sound effects for a speech he was giving to the American Society of Actuaries with the snappy title, “How Dead Are You? When You Die at 9:00 at Night, is it Fair to Count You as Dead the Whole Day?” He thought rolling thunderclaps and dirge-like renditions of “Pray for the Dead and the Dead Will Pray for You,” would liven it up some, so I went looking for a recording studio in town and found one kitty-corner from the local post office. The place was called “Eardrums,” and was run by a bunch of aging hippies who made a living doing commercials. They hung around after hours and invited in guys (and, they were exclusively guys) who would never get major-label deals, but still had enough chops to bribe the owner, Mick Slick, (obviously not his real name) into burning some two-track tape late into the night, just to see what they’d get.

The evening I went to scope it out, a long-haired, bearded guy in a gray overcoat who looked like he’d died decades ago in a shipwreck, was recording something on a hand-held, elec- tronic reed instrument that sounded like an air-raid siren wail- ing away in a bathtub full of crankcase oil. I figured it was what an approaching ambulance must sound like to old people with perforated eardrums. It was pretty painful, and when he finished up, Slick, who looked like a fraudulent country preacher, all curly hair and flashy teeth, came out of the studio to ask me if I was the guy from the Bean-Counting Agency.

“Those are accountants,” I said. “Actuaries analyze numbers and predict outcomes.”

“Sounds exciting,” he said, but I think he was joking, because he was giggling so hard he started crying.

We did our business, me signing up for a few hours of sound effects recording, Slick ridiculing me for working with a fart old enough to think haunted house screams were amus- ing, and then we got around to discussing the fate of the music business. Slick thought the major labels had monopolized dis- tribution, so we all had to listen to no-talent meatballs who were spewing out techno-pop, drum-machine and synthesiz- er-saturated, movie-soundtrack knock-offs. I had to confess that I lacked perspective, since I hadn’t bought a record album since the early sixties, when I picked up “Bustin’ Surfboards” by the Tornadoes, in a used records bin, and I’d done that with bottle-deposit nickels, just to set things in the proper era.

When I mentioned in passing that I’d once been a musician, Slick said, “Then you have the chops. You should start your own record label and be a producer—anybody can do it, and you look at home in a necktie and socks. The recording time is cheap if you do it in the middle of the night.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell him I’d only played the oboe and the bassoon, two instruments you can’t even use with an open instrument case collecting pennies on a street corner, let alone developing chops.

But he was on a roll: “The key is to just do instrumental stuff, no words, ‘cause then you can distribute international and you don’t need to overdub the lyrics. I know an outfit that does Scandinavia. Those people are freezing their asses off and will listen to anything.”

When I reminded him the music business was dead, how he’d just complained that the major labels had locked up distri- bution, he replied, “The Mob is still distributing the independent labels, and they bribe the retailers and the D.J.’s, so their stuff gets airplay and display coverage.”

His version of Hope Springs Eternal, I guess.

A rational person would have given up and gone back to work, but, like I said, I was bored.

“Isn’t most of the real talent in L.A. and New York?” I asked.

“Lots of undiscovered talent right here,” he offered. “Steege Funderbunk, World’s Best Guitarist, is in the studio right now, over in the Hot Room.”

“Nobody’s really named ‘Steege Funderbunk’,” I challenged, just to show him I wasn’t a complete chump.

“Parents were, like, Dutch windmill keepers, or something,” Slick responded, walking us down the hallway to the Hot Room, which had clay-tile floors and wooden walls and ceiling, so it had natural reverb that made everything sound like yodeling in the Grand Canyon.

We looked through the observation window from the con- trol room, and saw a tall, thin, bearded dude holding a guitar, neck up, leaning into the microphone, so it was almost touching his face. Slick turned on the monitor, and suddenly the man’s voice kicked in.

“BACON,” he said, loudly, like it was the answer to a test question, and then he proceeded to make crackling sounds of stuff frying in a pan, into the microphone, an effort that sounded authentic but had to be soaking the microphone with Funderbunk’s DNA.

“CAR WASH,” he announced, followed by a mix of rum- bling, suds and spray rinse sounds that sounded just like being trapped in your car as it went down the course of an automated car wash.

“Dude,” Slick said, pressing down a switch on the panel, “there’s somebody I want you to meet,” and Funderbunk put down the guitar and walked out into the monitor room.

“Want you to meet Douggie Shostrum, record producer from downtown—”

Nobody’d called me “Douggie” since Cub Scouts. “Uuhh, I’m not really—” I began, when he interrupted.

“You like the sound effects?” Funderbunk asked, as he shook my hand. “I guess…..” “You should hear my act. I do eight shows a week at the Tiki Room, me an’ Antonio Shamira.”

Rather than disappoint the guy, I agreed to catch his act, and later that week I dropped into the Tiki Room, a bar on the north side, full of drunks not really listening to the duo. A lot of the patrons were arguing, shouting or breaking empty beer bot- tles on the floor, barely noticing the guitarists. Funderbunk and Shamira were playing amplified electric Hawaiian stuff, designed to lend atmosphere to the place. They were wearing loud-colored shirts unbuttoned to the navel, weird eye make-up apparently designed to make them appear “More Hawaiian,” they later told me, and fuzzy tufts under their shirts I learned were chest wigs the proprietor made them purchase with their own money.

The music sounded awful, but I shared a cab home with Funderbunk anyway, who guided me up a flight of stairs to a room above a coach house that I would have sworn was unheated. He made me an open-face, toasted mustard sandwich, his regular fare, and I noticed he had musical scale paper taped on the walls around the room.

“What’s with the sheet music on the walls?”

“I write stuff down, play it once, then rip it down and throw it away. Nobody gives a shit.”

I pointed to one of the sheet rolls. It was marked “The Abandoned Highway”. “What’s this?”

“It somethin’ I did this morning.”

“Play it,” I asked, and he did. I thought it was remarkable, nothing like the stuff from the Tiki Room, just unamplified solo guitar sounding like what you’d think the atmosphere around an abandoned highway might sound and feel. I had him play a few more, and by morning I had worked my way through over a dozen of his current songs, tossing out a few, selecting others.

“Can you cash a check?” I asked. He nodded. “Here,” I said, handing him a check I quickly wrote for two hundred dollars. “Stay here for two weeks and rehearse this stuff, then meet me at Eardrums for some midnight sessions, starting the 25th.”

He pocketed the check. “You lookin’ for anybody else?” he asked.

I nodded.

“There’s this piano guy, Ted Wachitz, does the accompa- niment for the Diggers Theater. Good improviser. You should check him out.”

Wachitz looked a little more distressed than Funderbunk. He was older, probably pushing forty, wearing an open vest over a tee shirt. He had a paunch, a comb-over and a dirty, stubbly beard. The overall effect was a little like a middle-aged Winnie- the-Pooh, gone to seed. When I got to Diggers, where he was rehearsing, I immediately heard him roaring up and down the keyboard, obviously showing off, but I had to admit, he could play. He did have an annoying habit of loudly groaning every time the music got softer, sort of a phony-orgasm-at-the-pi- ano thing.

When I explained that I was putting together a roster of soloists for a new instrumental label, he immediately launched into his idea for a concept album, something he’d been working on, “at the request of his fans.” He played me a few of the selec- tions, and there was no denying he had a remarkable sense of touch, even if some of it sounded a little like he was noodling. When I made him the same offer as Funderbunk and directed him to Eardrums, he smiled, folded the check into his pocket, then told me he had his own engineer, who was also his agent, and that he could only record on a Hamburg Steinway piano in an acoustically perfect concert hall.

A rational person would have given up and gone back to a desk and a calculator, but I was getting all full of this record producer stuff, so I agreed to meet with his agent.

The “agent” was a studio recording engineer named Rex Sessions (obviously not his real name), who insisted I come to his apartment after work. He was older, balder and paunchier than Wachitz, and for some strange reason he cooked meatloaf for the occasion, as he spelled out the piano-man’s demands. They were: Total creative control, Tendra-Master quality record- ing (which I later learned was some contraption only Sessions owned), Hamburg Steinway Grand Piano, and isolated recording in Calvert Hall, the three-thousand–seat concert pavilion at State University, home to the local Philharmonic.

“Sounds expensive,” I speculated, to which he added, “And, union scale for the recording time.”

I had a lawyer friend draw up contracts (“Have you lost your marbles?”); negotiated the recording time, and then, while they rehearsed and prepared, I researched the process of getting a recording from the studio, to records and cassette tapes in distribution. The local Institute of Technology had a thorough section on commercial recording, going all the way back to Edison, whose technology, I learned, we were still using.

I spent my two-week paycheck to reserve mastering time (the process of carving the tape-fed signal into a lacquer disc that would form the “female” original from which record stampers were made); hired a stamper manufacturer in New Mexico; then signed up a pressing plant in California and a jacket manufac- turer in a local industrial park. It seemed too easy to be true.

The fateful Sunday evening at Calvert Hall rolled around, and as Sessions and I wheeled the Hamburg Steinway out on the stage and wired the microphone stand for sound, Wachitz suddenly developed an appetite.

“Uuhh, say, uuhh, could one of you guys get me an egg salad sandwich?” he asked, in a sort of imperial way.

“It’s after midnight, and we’re in the middle of a deserted college campus, cleared out for Summer break,” I replied, hop- ing that would be the end of it, but he insisted, so I found a still open sandwich shack a mile away, one that made a tuna-fish hoagie, which he gobbled up, even though he said “We screwed up his order.”

When we started tape rolling, he said, “I hear something up in the rafters,” so I climbed around the catwalks high over the stage, found nothing, then lied and told him I’d turned off a major fan humming away up there.

At 1:00 A.M., he finally started whacking away at a few selections, and it became obvious he hadn’t practiced any of them, and the studio time, at Union Scale, was his rehearsal. Most tracks took a dozen takes, and while we’d eventually get a keeper, it was usually marred by a loud groan, uttered at a pia- nissimo passage quiet enough so you could plainly hear it in the background. On the playback, it sounded like a guy, a mile away, getting run over by a car.

“What do we do with the groans?” I pleaded with Sessions.

“We only got the place until seven o’clock in the morning. Mess with his thing, and we’ll be down here all month.”

So, we did our best to select tracks where the groaning was faint enough so as not to send the listener to calling 9-1-1. We took a few pictures to use on the album cover and the cassette box, then packed up and went to Eardrums, to edit and remix the four-track tape and compose the album cover from the shots in the concert hall.

I asked Wachitz for some song titles, and that’s when the real trouble began.

“Let’s call the first track, “Agnieszka—”

“Is that Polish?” I started to ask, figuring he was done, but he was just getting started.

“Agnieszka was a beautiful Polish Princess, who enchanted all she charmed with her seductive, erotic dance, her veils swirl- ing around—”

“That whole thing?” I interrupted. “You want to call the first track that whole erotic dance thing? I think there might be space limitations if we have to do ten of those and still fit a blow-up of you at the piano.”

“I want a full-frontal head shot,” he injected.

“On the back? Scrunched in with all the track and tech information?”

“Yeah. And you guys did a terrible job—the camera loves me, and the proofs make me look old and fat. You ‘gotta get somebody in to touch those up.”

I decided to change the subject. “I was thinking, for an album title—”

“Piano Messiah,” he demanded, interrupting.

“Piano Messiah?”

“Yeah, I’m connecting on that level, don’t ‘ya think?”

“Hmmmm,” I offered, trying to think fast and save the entire project. “Aren’t you a little concerned that the religious types will be offended? I mean, remember when John Lennon said that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ, and people were all over the guy, burning copies of ‘Meet the Beatles’ in Times Square?”

“Good point,” he said, but just as I was sensing my first vic- tory as a record producer, he offered, “How ‘bout ‘Piano Savior’?”

I was obviously not getting my point across.

Meanwhile, the middle-of-the-night recording time was getting to me—I was fried the next day, and was screwing up at my day job.

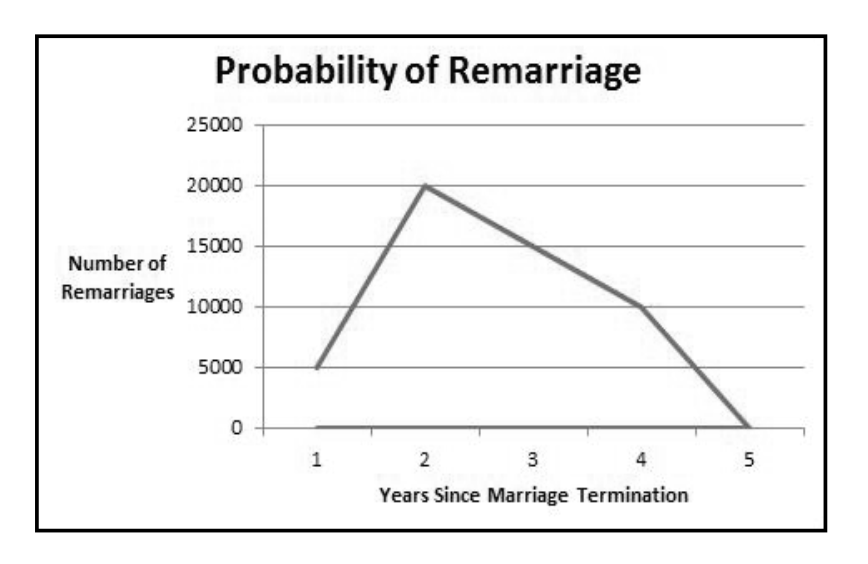

I’d mix up the axes on my graphs, and instead of telling people the average age at which women give birth in Ohio, I’d end up demonstrating the average age of the babies when they were born, which, when you think about it, is not very useful information. I’d go back to the Studio at night, and there’d be Funderbunk, settled in at Eardrums, dutifully recording each track, a few bad notes in some takes, but overall fairly efficiently. He’d decided to call his album “High Strung”, which was fine with me, after battling out Wachitz’s title woes, and ending up with “Key Man,” which sounded more like life insurance to me, but Wachitz grudgingly went along, after I put my foot down on the Messiah/ Savior stuff. No way was I going to start out with a boycott by Baptist Ministers, picketing outside our doors, just to humor some delusional musician.

I’d rented a small office in the same building as Eardrums, albeit pessimistically for the shortest period the landlord, a local butcher, would offer. I’d set up a corporation and called the whole thing “Joyful Noise Records,” a phrase I lifted straight out of the 98th Psalm (I may have flunked out of Seminary, but at least I did some of the reading). Like most creative folks, I figured the hard part was coming up with a distinctive and creative product; what I learned was that creativity was the easy part. Getting the stuff into human hands was the real challenge. Once I’d started doing that research, I quickly hired an out-of-work busboy as a full-time promoter guy/office guy/everything-else-I-couldn’t- do-and-keep-my-day-job guy.

Rip Paymaster (obviously not his real name) was a six- foot-seven farm boy and out-of-work busboy from Horseshoe County South Dakota, in town to get out of Horseshoe. He was an enthusiastic employee, although, in retrospect, it’s not that hard to be an employed busboy, so I should have been suspicious. While I scouted a few additional acts, once we had records and tapes, he started setting up free concerts on college campuses. He arranged to get promotional copies to college radio stations, and started going door-to-door to retailers, talking up the new label, hoping to get in-store display space. This part seemed to go well, given that neither of us had any experience, but he hit a roadblock when the first bulk inventory came in and he drove it out to our wholesaler, Dead-Head Distributions.

“The loading dock guys wouldn’t take it,” Paymaster reported, when he returned, dejected, from the drop off.

“We have a contract—they’re required to take it,” I com- plained, fortunately within earshot of Mick Slick, whose Eardrums studio shared an office reception with Joyful Noise.

“I told you they’re Mob—you ‘gotta bribe those guys,” Slick offered, looking at us like we were a couple of simpletons.

“I thought you said they did the bribing.”

“On their end. You ‘gotta bribe the dock guys to take your stuff. Just bring ‘em a couple a cases of beer,” he said, which sounded nuts to me, but, sure enough, when Paymaster tried that, they enthusiastically unloaded the stock. They did start drinking the beer, and midway through the operation they got a little carried away and ripped open a box of ‘33’s, took a few out of the shrink wrap and started throwing them around the loading dock like Frisbees.

I took in Wachitz’s first free concert, which was well enough attended, being the only thing on the local college campus happening that weekend, but then he got up on the stage and started talking. He was about as articulate as your average middle schooler, repeatedly asked for requests from the album, which was not yet in stores, and he kept scratching his privates as he paced around onstage. Since nobody knew the names of the album tracks, one person, impressed with the determination of Wachitz’s privates scratching, shouted out, “How about ‘Ass- Scratch Fever’?”, and I had to quickly check my copy of the album jacket to make sure that wasn’t one of the rambling, asinine titles Wachitz had insisted we use. My fiancé, Long Tall Sally (not her real name, either), who was also in attendance, pointed out it was obviously an homage to Ted Nugent and his similarly titled “Cat–Scratch Fever,” but I think the audience guy was just having a good time at our expense.

I was getting a lot of interest for “Key Man,” but not much for Funderbunk’s “High Strung,” I guess because piano is easier for people to warm up to than solo guitar. Record Store feed- back indicated that folks also inexplicably liked the fake-orgasm sound effects. Rip Paymaster insisted we needed a real promoter with experience to drum up talk of both records, and he found me a guy named Rick Barter (actually, his real name) who knew “everybody”, and for Five Thousand Bucks he could talk up the records with everybody that mattered. I should have seen it coming when Paymaster insisted Barter had to be paid in cash, and sure enough, Barter had a drug problem, which he also used to inoculate Rip Paymaster, and soon they’d both blown the Five-K, each had lost twenty pounds, and they were asking for more cash.

About the same time, I received a subpoena from the Federal Trade Commission, demanding that I turn over our cor- porate records (“What corporate records?”), and testify before a Commissioner about alleged cash bribery of radio professionals and retailers (they didn’t seem to care about the beer for the wholesaler). When I asked Paymaster what that was all about, he sighed and said, “I figured that guy was wearing a wire”.

Then I started to get airplay statistics from BMI and sales figures from the wholesaler, and as fate would have it, people were actually gobbling up Wachitz’s record, while Funderbunk’s sat in un-opened boxes. I ordered another pressing of “Key Man”, but when it arrived, Federal Agents cornered the van in the parking lot behind the office and seized the entire inven- tory. Distribution was drying up, and then the Mob-owned wholesaler, sensing the heat, dropped us. We could have gotten more copies of the stuff into human hands by dropping the albums and tapes on peoples’ heads out of a helicopter, flying around downtown.

I was facing indictment, so my fiancé insisted we hold a ceremonial bonfire and burn all the product, which we did, in a flaming trash can behind the studio. I went to lock up the office (Paymaster was in rehab) and turn in the keys, but I stopped to collect our last mail. Turns out Wachitz was jumping to a major label, something that was only possible because my lawyer had not obligated any of the artists to do more than one record, fig- uring “Nobody’d want to sit through more than one gig with any of these reptiles.” I also learned we’d won a Grammy for “High Strung”, although it was one of those tech categories they hand out in private, a month before the televised ceremony. Long Tall Sally didn’t even want to look at the thing, the whole affair just pissed her off, so now I use the Grammy as a doorstop, and when people ask, “Is that thing a Grammy?” I tell them, “Yeah, Elvis hocked it last week at the Grab-N’-Go where he works.”

And, now I’m back to the actuarial gig, getting all worked up just thinking about numbers and trends, like the mortality figures on left handedness, and how lefties die, on average, eleven years before righties born at the same time.

Actuarial science suddenly seems a lot sexier than it used to be.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet hendrerit massa velit.”